In the first post on forgiveness, I offered a few psychological definitions of interpersonal forgiveness in terms of changing motivation, transforming emotions, letting go, and cancelling debts. While these understandings of forgiveness vary and are not unanimously accepted, they remain helpful working definitions. To proceed further, however, it’s helpful not only to understand forgiveness as a process, but also to identify the conditions that are conducive to it. This is somewhat reminiscent of the way the fathers look for the mothers of a passion or of a virtue in order to help Christians walk in holiness.

As we explore the notion of forgiveness and how it relates to our own experience, an important question to ask is why some people let go of the need to retaliate more quickly, while others turn very slowly towards reconciliation. Why do some people hold onto an offense, while others let it go and move on? Why can some people readily express forgiveness even in the most trying of circumstances when others seem to be unable to forgive for the slightest offense?

Riek and Mania, in their article entitled, “The Antecedents and Consequences of Interpersonal Forgiveness: A Meta-Analytic Review,” have postulated that there are antecedents or pre-existing conditions before an offense takes place that make one more, or alternatively less, disposed to forgive others. The authors organize these antecedents by grouping them into personal influences, relationship-specific influences, offense-specific influences, and social-cognitive influences. For the purposes of this post, I will examine the personal influences. In the next few posts, I will review the remaining influences.

According to Reik and Mania’s analysis, personality plays a background role in disposing one to forgive regardless of the particular situation or the nature of the offense. They write, “The least proximal category of antecedents includes personality and individual difference factors, which are likely to be those that predispose a forgiving attitude. These will not be situational or offense-specific factors of an incident; rather, they will be somewhat constant within an individual. The next least proximal category includes factors involving the victim’s relationship with the offender.”

Riek and Mania note that studies have shown that individual personality plays a role in determining one’s disposition to forgive another. They conclude that the more generally agreeable personality will be more disposed to forgive than the more neurotic personality. In other words, someone who is soft-hearted, trusting, generous, acquiescent, lenient and good natured will be more likely to forgive than someone who is worrying, temperamental, self-pitying, self-conscious, emotional, and vulnerable.

“As McCullough and colleagues (1998) postulate, agreeableness and neuroticism may impact forgiveness by shaping the way a person interprets events and relationships. For example, someone high in agreeableness may be more willing to overlook certain offenses, while the negative emotions and views of someone high in neuroticism makes forgiveness more difficult. . . Other personality variables that have been explored are narcissistic entitlement, trait anger, attachment, empathy, and the cognitive need for structure. When people are high in narcissistic entitlement, they tend to be less forgiving (Strelan, 2007a). From a theoretical perspective, as the focus of narcissists tends to be themselves rather than relationships, a relationship repair device such as forgiveness is likely undeveloped. In addition, those high in narcissistic entitlement tend to be less supportive of unconditional forgiveness (Exline et al., 2004). Similarly, those high in trait anger are less likely to forgive transgressions (Berry et al., 2005; Exline, Yali, & Lobel, 1999) and those who are high in a need for structure tend to be less forgiving (Eaton, Struthers, & Santelli, 2006).”

Fortunately, among the five major traits of personality, researchers have found that agreeableness and neuroticism can and often do change as one ages. And there is no better way to affect that good change than to follow the very commandments of Christ, which encourage us to trust Him, to scorn self-pity, to have compassion on others, and to be flexible. Above all, we need to fight against philautia, that sickly love of self, which in the words of Saint John Chrysostom, is a great hindrance “to our perceiving what is just. Because of this (philautia), when we are judging others, we search out all things with strictness, but when we are sitting in judgment on ourselves, we are blinded” (Homily 36 on Matthew). If we desire to become more forgiving, according to the fathers, we need to become less self-centered and more Christ-centered. Then, we will see clearly enough, love fervently enough, and trust boldly enough to forgive.

According to Saint Peter of Damascus, the commandments of Christ are precious gifts that can deliver our souls from both traps of the enemy and those of our own making by teaching us to be watchful about our inner state (On Discernment). Doing as Christ suggests in the area where our free will is strongest—the attention we give to a thought— in turn makes keeping the ancient commandments of the law as epitomized in the Ten Commandments nearly effortless. This is especially clear in Christ’s commandment about anger. As Saint John Chrysostom notes, “He who is not stirred up to anger, will much more refrain from murder; and he who bridles wrath will much more keep his hands to himself. For wrath is the root of murder. And you see that he who cuts up the root will much more remove the branches; or rather, will not permit them so much as to shoot out at all…. for he that aims to avoid murder will not refrain from it equally with someone who has put away even anger; this latter being further removed from the crime” (Homily 16 on Matthew).

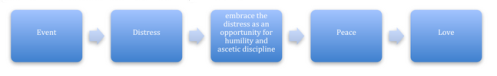

And yet how can one refrain from becoming angry, when becoming angry seems like and certainly feels like not only a natural response in many situations, but sometimes the right response. Again, we need to slow down and look within. Cognitive theorists have already done so and provided a sequence of steps leading from an unhappy occurrence to an angry reaction that can be seen in the following flowchart:

Something distressing happens that seems to be caused by the negligence, deficiency, or even malevolence of an offender. This makes us feel bad about ourselves, often wounding our overweening pride and exposing our demanding neediness. We feel that there is a wrong that needs to be made right. We become angry and in anger we retaliate.

Fathers, such as Abba Isaiah, suggest that it is possible to not become angry with our brother if we understand that anger is a dispute based on a lie and on ignorance (The Gerontikon, PG 65.180). We are not as important as we think we are and others are often not as malevolent or negligent as they seem. We cling so tightly to what boosts our egos or makes us feel good that anything that pries us from these false idols can enrage us. The problem, then, is not really the event that distresses us, but our inner passions that besiege us. According to Saint Maximus, if we would only despise glory and pleasure, every pretext for anger would be cut off (Chapters on Love, 75). Put in positive terms this means that we can avoid anger by embracing distressing situations as opportunities for humility and ascetic hardship, which can allow us to continue to move forward in peace towards an even greater virtue, being love itself. “Love,” according to Saint Isaac the Syrian, “does not know how to be angry or provoked or passionately reproach anyone” ( Homily 5). In other words, the fathers envision another pathway that starts in the same turmoil but ends not in a readiness to attack, but in a willingness to love. If we were to schematically present this patristic pathway it would look something like this:

What is of prime importance is that at the point of distress we learn another way of interpreting the situation considering the aim of the Christian life and welcoming the labor for virtue that is placed before us, learning as Saint John Chrysostom wrote, “to snuggle up to virtue, even though she causes us pain and to spurn vice, even though she gives us pleasure” (Homily on Acts 17). And if that aim seems too high for us in our slothful and indulgent state, we can at least turn to the words of our Savior as a rock upon which to build our house. For example, Saint Barsanuphios suggests that we courageously endure every distress by establishing ourselves firmly on the encouraging words of the Lord: “In the world ye shall have distress; but be of good cheer, I have overcome the world” (Letter 22). If we chart out that cognitive pathway, we again find ourselves reaching the blessed harbor of love:

The watchful and committed Christian always has choices, beautiful, inner choices of the heart, which can lead to places of peace, harmony, and love. They begin by listening to our meek Lord’s commandments that may seem to go beyond the limits of human possibilities, because in fact they do. Through His commandments, we do indeed go through the fire of insults and through the water of disgrace, but He brings us to a place of refreshment (Psalm 65:12, LXX). And suddenly our inner world and our outer interactions are radically and wonderfully changed: where there was not only anger, but also a readiness for violence, now there is “the peace of God, which passeth all understanding” (Philippians 4:9) and “the love of Christ, which exceeds all knowledge, so that we might be filled with all the fullness of God” (Ephesians 3:19).

In a fallen world, no one escapes the bumps and bruises associated with our interactions with others. Sometimes, the cuts and scrapes form gaping holes that may leave us offended and wounded, hurt by angry words, callous actions, or selfish disregard. While we can confidently affirm that conflict is an inevitable, if not unfortunate part of human life, the aftermath of such often comes down to a choice between resentment and forgiveness. This new blog series will focus attention on the latter.

Forgiveness, or the lack thereof in ourselves or in others, is a subject that affects each of us, undoubtedly on a daily basis. Its role is so significant that psychologists and healthcare professionals over the past thirty years have begun studying what people of faith have known about for millennia, namely that forgiveness plays a powerful, therapeutic role in better physical and mental well-being. Of course, Christianity uses another language—the language of the heart, the language of brotherhood, and the language of God Himself—to speak about forgiveness, whereas psychology uses the terminology of science. Is there a meeting place between our forgiving our brothers and sisters from our hearts their trespasses against us (Matthew 18:35) and what psychologists are exploring today? That will be one of the questions this series will attempt to answer.

A starting point for that question would be to look at some definitions that psychologists propose for forgiveness. As Blake Riek and Eric W. Mania have noted in their article “The Antecedents and Consequences of Interpersonal Forgiveness: A Meta-Analytic Review,” there have been various opinions concerning an exact definition of the term. Yet, they do point out the definition put forth in 1997 by McCullough, Worthington, and Rachal: forgiveness is “a set of motivational changes whereby one becomes a) decreasingly motivated to retaliate against an offending relationship partner, b) decreasingly motivated to maintain estrangement from the offender, and c) increasingly motivated by conciliation and goodwill for the offender’” (pp. 321-22). In other words, forgiveness is about how we are moved with respect to someone else or a change in disposition in which the fight or flight impulse has weakened and an inclination towards meeting the person with kindness begins to grow stronger. There is a change in the will and a change in perspective that allows for a radically new and undeniably positive approach to someone else that is manifest in thoughts, emotions, and behavior. That this is something good, almost goes without saying.

Others have understood forgiveness in terms of letting go of past hurt and bitterness, (Berecz). After all, the English word forgiveness etymologically comes from the Germanic vergeben meaning to abstain from something (ruminating about the hurt) and to give it away. Still others view forgiveness as the removal of negative and introduction of positive emotions toward an offender. The sense of relaxing tension meshes rather well with a willingness to give up the necessarily tense states of fleeing from others or fighting them. Exline and Baumeister (2000) understand forgiveness as debt cancelation by the victim. The cancellation of debt has particularly strong Christian overtones, but leaves out some powerful elements: the presence of God and the need for humility. For instance, Saint Cyril of Jerusalem would comment on the verse “And forgive us our debts as we also forgive our debtors” (Matthew 6:12) as follows “For we have many sins. For we offend both in word and in thought, and very many things we do worthy of condemnation; and if we say that we have no sin, we lie, as John says. And we make a covenant with God, entreating Him to forgive us our sins, as we also forgive our neighbours their debts. Considering then what we receive and in return for what, let us not put off nor delay to forgive one another. The offences committed against us are slight and trivial, and easily settled; but those which we have committed against God are great, and need such mercy as He alone can give. So, be careful lest for the slight and trivial sins against you you shut out for yourself forgiveness from God for your very grievous sins” (Catechetical Lecture 23).

The value of these psychological definitions is that they draw some sharp lines that we can use to look inwardly and decide whether we have forgiven someone else. If we are tense around someone who has hurt us and feel the urge to flee or alternatively if we have to control ourselves in order to not lash out, if we hold onto the offense with the clenched fist of our mind, we have not yet begun to forgive. Psychology tells us that much. As for theology, it opens up other horizons in the soul through which the impossible becomes possible. With this introduction in mind, let’s begin to explore the topic of forgiveness.

For I say unto you, That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven.

One of the first lessons we are taught as children is that some things are right and other things are wrong. There are rules to follow at home. There are rules to learn in school. There are rules for the games we play. There are rules for just about everything. And if we obey the rules, we can become good little boys and girls. We can do well in school. We can win the game. And so we all learn to be very good at the rules. That’s why we rehearse the rules in our minds, write them down in our hearts, and follow them in our day-to-day lives. Isn’t that what being a good person is all about?

One of the first lessons we are taught as children is that some things are right and other things are wrong. There are rules to follow at home. There are rules to learn in school. There are rules for the games we play. There are rules for just about everything. And if we obey the rules, we can become good little boys and girls. We can do well in school. We can win the game. And so we all learn to be very good at the rules. That’s why we rehearse the rules in our minds, write them down in our hearts, and follow them in our day-to-day lives. Isn’t that what being a good person is all about?

Not according to our Savior. Yes, we are to keep the commandments of God and let them illumine us as we saw last week. Nevertheless, simply writing down the rules (being a scribe) or acting according to them (being a Pharisee) is not enough. The goodness of heaven requires something more than the rules of earth. Like the sky above, the righteousness of God has an expansiveness that opens its arms even to the unwelcome and a freedom that allows even the wingless to soar.

According to Saint Cyril of Alexandria in his commentary on Saint John, the rules prepare us for a new way of being in Christ, but if we get stuck in the rules we remain as children playing in the shadows. This is especially true concerning the rules about love. In the law, there are beautiful and holy commandments about this the highest of virtues. In particular, Deuteronomy 6:5 declares, “And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might,” while Leviticus 19:18 states in the context of grudges, “thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” And yet the righteousness of Christ requires something more that He Himself reveals when He taught His disciples, “A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another” (John 13:34).

What is new about Christ’s love? Its inclusivity, its magnanimity, and its flexibility that defies all rules, even the most holy ones, knows no boundaries, even those set in stone, and values each soul, even the greatest outcast, more than the entire world. Some psychologists define psychological flexibility as “contacting the present moment as a conscious human being, fully and without defense, as it is and not as what it says it is, and persisting or changing in behavior in the service of chosen values” (Hayes, Pistorello, & Levin, 2012). Doesn’t such flexibility characterize the way Christ encountered those in the Gospel, being fully present to the soul before Him and giving Himself fully to that soul, not being constrained by what that soul might have done, not being restricted by what others may think, not being limited by the rules of time and place?

The rules say the leper is untouchable, yet Christ touches him (Mark 1:41). The rules say, “the Jews have no dealings with the Samaritans” (John 4:9), but the Savior gives a sinful Samaritan woman the living water of the Holy Spirit. The rules say the “the adulteress shall be put to death” (Leviticus 20:10) yet the only Friend of the human soul responds, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” (John 8:7). What were the values that guided such freedom and flexibility? The will of the Father and the salvation of the world. Through them, He walked where rules would not permit, He opened doors that rules had tightly closed, and He transformed lives that the rules had relegated to stagnation and death. This is the kind of flexible single-mindedness (to join two words that are usually held apart) that should characterize Christian righteousness, the righteousness of the kingdom of heaven.

Flexible single-mindedness is what the Blessed Augustine was referring to when he said, “Once and for all, a brief precept is given to you: Love, and do what you wish: if you hold your peace, out of love hold your peace; if you cry out, out of love cry out; if you correct, out of love correct; if you spare, out of love spare. Let the inner root be love, for from this root nothing else can shoot forth except for that which is good” (On the First Epistle of John 7,8 PL 35.2033). This is the righteousness that knows how to bend down, that knows how to reach out, and that knows how to look up. It can’t be learned by repeating the rules, but only by learning to see beneath the surface, by learning to listen to the voice of the one who is speaking, and by learning to love even when that which is loveable can scarce be found. Through the grace of God Who is everywhere present and the love of Christ that fills all things, may we all dare to flexible enough to make such righteousness our own.

Reference:

Hayes, Pistorello, & Levin (2012). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Unified Model of Behavior Change. The Counseling Psychologist 40 (7), 976-1002.

From an early age, we are taught that we will be judged by our successes and failures. We are encouraged to study hard, make good friends, be polite, and take care of our health. All of these counsels are designed with one goal in mind: our success in life. When we fail, it is quite often assumed that failure occurred because we didn’t try hard enough or study diligently enough. We are made to believe that there is a one-to-one causal relationship between our effort and our success. However, we soon find out that life is much more complicated than that. Sometimes, there are paradoxical factors at work beyond our sphere of influence or control.

For example, when a novelist sits down at his desk and experiences writer’s block, more effort may only make the problem worse. When a professional baseball player has trouble hitting, trying harder often exacerbates the slump. The novelist and the baseball player may regain their former success after they have relaxed and chosen to walk away temporarily from the task at hand. Alcoholics have related that their attempts to remain sober failed until they re-focused their attention on helping others, rather than concentrating on their own inability to refrain from alcohol.

These solutions often seem paradoxical to those of us who believe hard work and effort are the only ways to achieve success, because they reveal that sometimes we need to act or react in unexpected, paradoxical ways that don’t seem to lead to our goal, yet somehow through the door of paradox we find ourselves already there. For those intent on the security of earthly riches, Saint John Chrysostom would suggest its paradoxical relationship with the wealth of heaven: “Despise riches, if you want to have riches. If you truly want to become rich, become poor. For such are the paradoxes of God” (Homily 11 on First Timothy, PG 62.555).

Paradox has garnered the attention of poets, philosophers, theologians, statesmen, and doctors for centuries. Some have sought to describe it while others have attempted to solve it. In his work entitled, Orthodoxy, G.K. Chesterton wrote, “The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life is an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is; its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait” (Chapter VI, “The Paradoxes of Christianity”). Belief in one-to-one causality trips us up in many aspects of life. It blinds us to the presence of inexactitude in our world and the reality of paradox that far from being a curse, is a blessing that opens up for us other possibilities.

Some cognitive behavioral therapists have focused their attention on paradox and attempted to employ it in treatment programs. For example, Lynn Petras Gould writes in her dissertation, “A Comparison of Three Cognitive Behavioral Treatments for Insomnia: Paradoxical Intention, Coping Imagery, and Sleep Information,” that employing the technique of paradoxical intention may actually help the insomniac achieve sleep. She writes, “Upon monitoring their level of arousal, insomniacs are apt to conclude it is prohibitively high. When attempts to lower arousal and achieve sleep prove unsuccessful, anxiety increases. This spiraling cycle makes sleep increasingly difficult to attain. In order to undo this process, insomniacs are instructed to exercise paradoxical intention. That is, instead of trying to fall asleep, they are told to try to remain awake as long as possible. The use of this paradoxical directive interrupts the exacerbation cycle by eliminating the goal of falling asleep. If the insomniac can refrain from trying to fall asleep, performance anxiety should diminish and sleep should occur more easily.”

The key element in paradoxical intention is the willingness to abandon control. According to Petras-Gould, “Behavior therapists employing the technique of paradoxical intention have adopted a model based on the concept of performance anxiety… Sleep, they observe, is not a completely voluntary phenomenon. One can provide conditions facilitative of sleep, but at some point, must abandon control in order for sleep to occur. Insomniacs, however, continue their attempts at control, thereby impeding the onset of sleep.”

For some readers, the notion of paradoxical intention is a new therapeutic concept. For others, especially those associated with Alcoholics Anonymous and traditional Christianity, the practice is an integral part of remaining sober or living a Christian life. For instance, the first three steps of Alcoholics Anonymous are concerned with abandoning control: “We admitted we were powerless over alcohol”, “a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity” and “we made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God…” The sacred Scriptures are even more explicit and call for radical abandonment and relinquishing of control, “for whosoever will save his life shall lose it: and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it” (Matthew 16:25). The Psalmist anticipates the teaching of Christ in Psalm 146 (145 LXX): “Put not your trust in princes, nor the sons of men, in whom there is no help. His breath goeth forth, he returneth to his earth; in that very day his thoughts perish. Blessed is he that hath the God of Jacob for his help, whose hope is in the Lord his God.”

Life indeed is full of paradox, full of reversals, full of the unexpected. Accepting this reality and even embracing it, changes the equation for insomniacs, alcoholics, and Christians. We all have a choice other than running headlong into a wall that doesn’t budge. We can abandon control over those things of which we have no control and turn our gaze towards God’s glory and His providential designs for each of us. In so doing, we might discover a door in the midst of that wall that we had never seen before, beckoning us to open it and walk on through. All it takes is a willingness to let go and do something new.

![]() Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven: but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

Whosoever therefore shall break one of these least commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven: but whosoever shall do and teach them, the same shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

Human beings are marvelously complex. In the myriad of situations in which we find ourselves, with the multitude of people with whom we interact, we can respond in thought, word, and deed in a variety of ways with a range spanning from the darkest hell to the brightest heaven. Choices confront us at every moment and the decisions we make determine the people we become. We can align our will with our whims and blow about like a leaf in the wind with no final destination other than being eventually trampled underfoot. Or we can try to align our will with the will of God and thus become ruled by God, guided by God, and ministers of His presence in the world. This is the context of Christ’s comments on the dangers of breaking the least of the commandments and teaching others to do so as well as the glories of fulfilling them and teaching one’s brethren to do the same.

According to Saint Irenaeus, when a person breaks a commandment, the heart is darkened, God is forgotten, and the individual begins to worship himself or herself as God (Against Heresies, Book 5, chapter 24). Having a hamburger on a Wednesday or a Friday, for instance, may seem insignificant to some. But for a conscientious Orthodox Christian, such behavior is a breaking of the Church’s fast, which reveals an indifference to the betrayal of Christ and His crucifixion or at least relegates these events to a distant past that no longer directly touches one’s daily life. God is forgotten, while one’s needs and desires fill the empty space in the soul where God should reside. And this disregarding of a commandment in turn will make it that much easier to disregard another commandment, and then another, until one is left with the secular morality of being a good person without any of the radiance and illumination that comes from the Christian faith.

Saint Augustine put it this way, “Believe the commandments of God, and do them, and He will give you the strength of understanding. Do not put the last first, and, as it were, prefer knowledge to the commandments of God… Consider a tree; first it strikes downwards, that it may grow up on high; it fixes its root low in the ground, that it may extend its top to heaven” (Saint Augustine, Sermon 68). Keeping the commandments, all of the commandments, can enable believers to grow strong like mighty trees and to have deep roots so that tempestuous temptations cannot blow them down. In the ancient Christian text, the Shepherd of Hermas, it is written, “if you keep the commandments of God, you will be powerful in every action, and every one of your actions will be incomparable” (Book 2, 7). They will be incomparable, for they will be Godlike and above all they will be loving, for all the commandments rest on the great commandment to “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind… and thy neighbour as thyself” (Matthew 22:37-39).

The divine and life-giving commandments of God (using an expression from canon law), even the least of them, are to be kept and to be taught because they alone on a moment to moment basis and in matters great and small can bring about a transformation in a person’s life, character, and ultimate destiny. They illumine us; they guide us; they initiate us into a mystery beyond human understanding. Through them, we come to know the image of God in man. As Saint Ambrose of Milan once wrote, “If, then, any one desires to see this Image of God, he must love God, that he may be loved by God; and be no longer a servant but a friend, because he has kept the commandments of God, that he may enter into the cloud where God is” (Book 2 on the Decease of his brother Satyrus, 110).

Whenever we encounter difficulties in life or whenever some unexpected suffering comes our way, our natural instinct is to find an immediate escape from that difficulty or suffering. When such an escape is not readily available or manifest to us, we may become despondent or begin to think the worst, which in psychological terms is known as catastrophizing. We can tell we’re doing this by the nature of our interior dialogue that we have with ourselves. That private conversation can aggravate an existent problem and generate new ones.

Whenever we encounter difficulties in life or whenever some unexpected suffering comes our way, our natural instinct is to find an immediate escape from that difficulty or suffering. When such an escape is not readily available or manifest to us, we may become despondent or begin to think the worst, which in psychological terms is known as catastrophizing. We can tell we’re doing this by the nature of our interior dialogue that we have with ourselves. That private conversation can aggravate an existent problem and generate new ones.

In his dissertation, “Treating Insomnia-A Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy Approach”, Alfonso Marino offers an alternative to the instinctual impulse to escape and engage in pessimistic rumination. Marino defines it as “positive self-talk” which he describes in this fashion, “Try to have a positive attitude towards your sleep and try repeating the following points to yourself: a) I have set aside time to deal constructively with my problems tomorrow. b) If I awaken early tonight, I will not dwell upon it, but will remain relaxed with my mind in neutral. c) Nightly arousals are normal. d) Developing these sleep habits took time, so it will also take time for them to return back to normal.” In other words, he suggests making true statements that normalize the situation and enable one to see that one’s plight, though highly unpleasant, is really not the end of the world.

This strategy has been applied elsewhere with varying degrees of success. For example, in Alcoholics Anonymous, newcomers are quickly introduced to various slogans (positive self-talk) to ward off the temptation to drink so that they are able to continue to battle their alcoholism especially during times of temptation or suffering. Slogans such as “One Day at a Time” or “This Too Shall Pass” are two examples that may be borrowed and adapted to the circumstances of the insomniac.

After all, suffering and difficulties are an inevitable part of our fallen human condition. They can’t be avoided forever and the goal should be to live in peace and tranquility in spite of them. The insomniac, the alcoholic, and anyone experiencing difficulties in life must shun the alluring temptation of the quick fix, be careful about the content of their inner dialogue, and live in the moment.

The rational, normalizing positive self-talk of cognitive therapy as well as the tried slogans of AA have their value, but there is, to use Saint Paul’s expression, “a more excellent way” (1 Corinthians 12:31). If we pray consistently and attentively, words from Scripture and the holy fathers well up in us during times of anxiety, stress, and sleeplessness. The words of Psalm 118 come to mind, “Give thanks to the Lord, for He is good; His love endures forever. . . When hard pressed, I cried to the Lord; He brought me into a spacious place. The Lord is with me; I will not be afraid. What can mere mortals do to me? The Lord is with me; He is my helper. I look in triumph on my enemies.”

Prayer cultivates and nurtures this remembrance of God of which the Psalmist sings. Prayer is a constant reminder that God is with us, most especially in our difficulties and temptations. He does not send them to us as punishment. Abba Dorotheos writes, “The person who truly comes to serve God must prepare his soul, as it says in the Wisdom of Sirach (2:1), for temptations. Thus, that he will never be surprised or disturbed by what happens, believing nothing that happens without the providence of God and where there is the providence of God certainly what happens is good and for the benefit of the soul. For, everything that God does, He does for our benefit and because He loves us and has pity on us. We must, as the Apostle says, ‘In everything give thanks” (1 Thessalonians 5:18), for His goodness. We must never be troubled or narrow minded about anything which happens to us but we must calmly accept everything which happens with humility and hope in God, believing, as I have said, that everything that God does for us, He does because of His goodness and it is never possible for things to be better than the way God arranges them in His mercy” (Lesson 13, “On the Suffering of Temptation Calmly and Thankfully”).

In prayer and the constant remembrance of God, we move beyond the mind’s rational self-talk to a recognition of God’s presence and love for each of us. We are brought to the realization that perhaps sleeplessness is beyond our power to control but God is with us and we trust that He knows what is ultimately good for us.

In Ancient Christian Wisdom, I compare and contrast cognitive techniques and spiritual strategies. “The fathers also advise the faithful to ponder how God blesses them materially, spiritually, temporally, and eternally, so that they will be moved to gratitude and motivated to lead the God-pleasing life of virtue. This kind of theoria alters their behavior. The centrality of this approach in Orthodox Christianity is evident in the placement of such a remembrance of the entire divine economy at the heart of the Divine Liturgy before the priest consecrates the holy gifts. From a psychological perspective, this theoria is a mental activity that therapists could call a cognitive technique. From a spiritual vantage point, however, it is a blessed and sanctifying use of the rational aspect of the soul and attracts the grace of God” (ACW, p. 197).

When our life in God is consistent and constant, in spite of the ebbs and flows of daily life, we remain undisturbed because we grasp what Saint Paul wrote to the Romans, “For I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:38). And even if we cannot yet fathom these words as deeply as we should, we can still begin by taking these treasures from Scripture such as these words from Saint Paul or the Psalms of David and make them our positive self-talk and our trusty slogans, gently and hopefully repeating them to ourselves again and again. In so doing, we can remain positive, we can feel calm, we can feel safe, and we might just fall asleep as well.

The maxim “our thoughts determine our lives” is central to our self-understanding as well as our ability to understand the choices we make each day. Thoughts are the interpretive tool through which we understand ourselves, others, and the circumstances of daily life. When these thoughts are good and wholesome, we are able to make critical decisions in the workplace, assist family members, and order our life according to the values by which we have consciously chosen to live. However, when these cognitions are harmful, our perceptions of self, others, and our environment become distorted which often leads to errors in our behavior or our perceptions of others’ actions. This is also true in terms of the cognitive role in achieving proper sleep and overcoming insomnia.

The maxim “our thoughts determine our lives” is central to our self-understanding as well as our ability to understand the choices we make each day. Thoughts are the interpretive tool through which we understand ourselves, others, and the circumstances of daily life. When these thoughts are good and wholesome, we are able to make critical decisions in the workplace, assist family members, and order our life according to the values by which we have consciously chosen to live. However, when these cognitions are harmful, our perceptions of self, others, and our environment become distorted which often leads to errors in our behavior or our perceptions of others’ actions. This is also true in terms of the cognitive role in achieving proper sleep and overcoming insomnia.

The scientific literature concerning the problem of insomnia is quite clear that our thoughts affect our ability to achieve sleep. Alfonso Marino has noted, “Going to bed with a racing mind will (sic) almost guarantee you disturbed sleep, if any. This anxiety reinforces that you were not able to sleep, which then causes further anxiety, which then perpetuates your inability to sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. Cognitive strategies try to help you to deal with your worrisome preoccupations and aim to replace them with calmness. The person who lies in bed and is constantly tossing, turning, and cursing that they cannot sleep, and “I’m going to be a wreck tomorrow!”, will (sic) only be perpetuating further anxiety, making sleep that much more difficult. Cognitive interventions try to focus on what patients think and tell themselves and correct irrational ‘catastrophizing’ thoughts with calming ones.”

The good news is that we can achieve some mastery over our cognitive life. We are not automatically enslaved by our thoughts. We have the ability to reject those harmful thoughts such as “I’m going to be a wreck tomorrow!” and replace that cognition with truths from Holy Scripture such as “I can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me” (Phillipians 4:13) With this truth from Scripture, Saint Athanasios the Great was able to say, “If tribulation comes, I shall endure it; if persecution comes, I shall be a martyr; if famine comes, the Word will nourish me” (On the Song of Songs, PG 27.1349). Certainly with that same thought, those suffering from insomnia can say, “If a sleepless night comes, I shall face the day!”

In writing about this process, Marino lays out a set of vignettes in which he names the dysfunctional cognition, the underlying belief, the cognitive errors in the underlying belief, and interventions or alternative interpretations. For the purposes of illustration, I will cite one of these. In “Vignette 7” Marino tackles the issue of “Diminished Control over Sleep and Performance Anxiety”:

Dysfunctional Cognition: “I am afraid of losing control over my sleep abilities. I have lost control over my sleep.”

Underlying Belief: “It is essential to be in full control of all aspects of one’s life.”

Cognitive Errors: catastrophizing, irrational belief

Interventions/Alternative Interpretations: “1) What is the worst thing that could happen if you never got to sleep tonight?

It is not catastrophic to go without sleep. 2) The harder you try to control sleep, the less control you will achieve; it is much easier to force wakefulness than to fall asleep at will. 3) Sleep will come more easily if you do not try so hard to control it.

These vignettes demonstrate the importance and value of determining and examining one’s thoughts. The holy fathers have recommended this practice for centuries and for good reason-no progress can be made if we are unaware of our thoughts and the underlying beliefs associated with them. Using Marino’s vignette as an example, once we recognize the thought and acknowledge its underlying belief about control, it becomes much easier to perceive the cognitive error and seek out alternative interpretations. The battle has to be engaged at the level of cognition, not action. Too often, those suffering from insomnia attempt to act before examining their thought patterns. Yet it is the thought patterns that exacerbate the insomnia in the first place.

“Chronic insomnia is seen as a symptom of a breakdown in coping and in adaptation. Emotional arousal is seen as being precipitated by unexamined, unresolved emotional conflicts.” (Marino, p.128) This is true for all conflicts and issues we confront in life, including insomnia. These emotional conflicts arise from dysfunctional cognitions which include catastrophizing, irrational beliefs, and misattribution, and absolute thinking.

For the Christian, the weapons of prayer and watchfulness play an indispensable role in coping with thoughts. Saint Theophan the Recluse writes, “Strive to keep in order your thoughts about worldly concerns. Try to arrive at a state in which your body can carry out its usual work, while leaving you free to be always with the Lord in spirit. The merciful Lord will give you freedom from cares, and where this freedom prevails everything is done in its own time, and nothing is a worry or a burden. Seek, ask-and it will be given.” (Art of Prayer, p. 237)

The goal of resolving cognitive dysfunctions is ultimately much greater than achieving restorative sleep. The goal is freedom from all those things that enslave us. In the words of Saint Paul, the ultimate goal is found in his words to the Romans, “Because the creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God.” As Saint Irenaeus echoes Saint Paul in writing, “For the glory of God is a living man; and the life of man consists in beholding God” (AH 4.20.7). This puts all our thoughts into a proper perspective, which in itself grants us peace.

Saint Gregory of Nyssa once remarked that nature “finds the body tense through wakefulness, and by means of sleep devises relaxation for this tenseness, giving the sense perceptions rest from their activity for a time, loosing them just like we release horses from the chariots after the race” (On the making of man, 13). Can there be a more apt analogy to the simple and natural art of falling asleep? Making use of this analogy, learning how to fall asleep is about learning how to let go of one’s thoughts, to let go of movement, to let go of winning, and to let go of purposeful activity just like a charioteer releases his horses to pasture after a hard day’s race. So much of our lives are about holding the reins tightly, that letting go of them sometimes quite paradoxically requires extra effort to exert no effort. One such effort often suggested by physicians and psychologists alike is relaxation training, a topic we have addressed in blog posts on chronic pain and type-A personality behavior.

The word relaxation is derived from the Latin word laxus meaning wide, open, loose, and spacious. It can be contrasted with strictus (the root for the English word for strict and related to the English word for strong) having the connotations of binding, holding tightly, controlling, and even attacking. As this concept relates to sleep, relaxation involves being in a place in body and soul that is wide, open, loose and spacious, which gently and naturally leads to a reduction of psychological, emotional, or physical arousal. As Alfonso Marino writes, “An integral component of CBT in the treatment of insomnia is relaxation training. Arousal interferes with sleep. Physiological activity must be reduced in order to initiate sleep. Physiological arousal may be manifested by a rapid heart rate or muscle tension brought on by frustration or anxiety over not being able to sleep (Freedman & Sattler, 1982). Similarly, cognitive arousal may be manifested through worry, rumination, intrusive thoughts and planning (Morin et al. 1999).”

Relaxation techniques may help reduce some of these symptoms, especially the physiological manifestations. Marino notes later in his dissertation that progressive muscle relaxation training is particularly effective in coping with physiological arousal. In terms of dealing with cognitive arousal associated with intrusive thoughts and ruminations, Marino suggests the use of guided imagery such as imagining a peaceful setting such as watching a sunset or “feeling the warm sun on your skin and the sand between the toes.”

For physical beings with active minds, this advice can be very helpful, but we are also spiritual beings for whom rest and peace is more than a matter of relaxed muscles and pleasant fantasies. Trust in God’s love, a perception of God’s warmth, and a sense of God’s Sabbath rest can bring a completeness to these bodily techniques and direct us to the open expanses in which relaxation can indeed be found. And in general, thoughts about beautiful aspects of creation such as the sea and the sunset can be springboards for a quiet and calming gratitude for the many gifts that our merciful Lord has already bestowed upon us. Gratitude makes us feel secure; gratitude makes the world seem a bit more spacious; and gratitude shifts our focus from our problems to the solutions that have appeared often unexpectedly on our laps. Without a doubt, gratitude can be relaxing. There are even contemporary studies maintaining this very point. But what is even more important for our purposes, gratitude, unlike pleasant musings, can be real, far more real than an imagined sunset and far more personal. It would seem to be the ideal complement for any Christian attempting to relax and go to sleep.

In the area of human sciences, laws of genetics and laws of behavioral interactions as well as rich descriptions of the processes that lead to sickness and to health are accepted by all as incontrovertible givens. Humanity conforms and acquiesces with nary a murmur or complaint. And yet with respect to moral values, the spiritual life, and liturgical practices, people feel that it is permissible, perhaps even desirable, to adjust and even discard the givens of faith, the givens of revelation, and even the givens of sin and holiness. It is as though the claims of science have such a hold on us that the claims of history and tradition may seem to be too much. And yet, the givens of faith can free the human spirit and open up horizons that scientific causality could never imagine.

In the area of human sciences, laws of genetics and laws of behavioral interactions as well as rich descriptions of the processes that lead to sickness and to health are accepted by all as incontrovertible givens. Humanity conforms and acquiesces with nary a murmur or complaint. And yet with respect to moral values, the spiritual life, and liturgical practices, people feel that it is permissible, perhaps even desirable, to adjust and even discard the givens of faith, the givens of revelation, and even the givens of sin and holiness. It is as though the claims of science have such a hold on us that the claims of history and tradition may seem to be too much. And yet, the givens of faith can free the human spirit and open up horizons that scientific causality could never imagine.

That is why the desire to re-fashion Christian teaching or find a “new way” of doing things is a temptation. When we hear comments such as “I worship God in my own way, I don’t need the Church or her teachings,” the tempting thought has been accepted and already acted upon. And although contemporary society might make this temptation appear more alluring and arise more frequently, it is not a new idea. Christ Himself spoke of that temptation when He said, “For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished.”

Saint Gregory Palamas in commenting on this Scripture passage wrote, “But this, you might say, is from the old law. What bearing does it have on us, the people of the new covenant? Have you not heard Christ, the Lord and lawgiver, saying, ‘I am not come to destroy the law but to fulfill’, and ‘One jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled’. If this is the case, anyone liable to the sentence of death and the other threatened punishments on account of sin, will of necessity be put to death, be shamefully defeated and delivered up to his enemies, and suffer every terror. There is only one remedy invented by the wisdom and grace of the only God and Savior Christ: to make ourselves dead to sin through repentance.” The givens of the Law guide one to a transfiguration in which what should be dead is in fact deadened and what should be alive is indeed made to live. Without that Law, however, one loses one’s moorings and wanders in one’s own personal pathless desert in which the dreamed of oasis is but an illusion of one’s own making.

The path to salvation is the same path trod by the holy martyrs of the early Church and the same path of its saints throughout the ages. To reject that path or adopt other paths is to begin a journey whose final destination is no longer sure. In fact, Saint Theophan the Recluse wrote a letter to his flock concerning the unchanging nature of the path towards salvation in 1863 when he received word of people grumbling about the strictness of his sermons. He wrote, “It reached my ears that, as it seems, you consider my sermons very strict and believe that today no one should think this way, no one should be living this way and therefore, no one should be teaching this way. ‘Times have changed!’ How glad I was to hear this. This means that you listen carefully to what I say, and not only do you listen, but you are also willing to abide by it. What more could we hope for, we who preach as we were ordered and as much we were ordered? Despite all this, in no way can I agree with your opinion. I even consider it my duty to comment on it and to correct it, since – even though it perhaps goes against your desire and conviction – it comes from something sinful, as though Christianity could alter its doctrines, its canons, its sanctifying ceremonies to answer to the spirit of each age and adjust itself to the changing tastes of the sons of this century, as though it could add or subtract something. . . If the saving power of this teaching depended on our opinion of it and our consent to it, it would make sense for someone to imagine rebuilding Christianity according to human weaknesses or the claims of the age and adapt it according to the sinful desires of his heart. But the saving power of Christian law does not at all depend on us, but on the will of God, by the fact that God Himself established precisely the exact path of salvation.”

The spiritual laws handed down through Moses and the prophets and fulfilled in Christ are not similar to civil laws, which may be adjusted or rescinded depending upon circumstances or the needs of the times. In a sense, they are more like the natural laws in which precise consequences follow when certain conditions are met. In other words, spiritual laws are not followed to please the crowd, but to heal the sick. And if health is identified as a good, it only makes sense to follow advice that leads to that good. Saint John Chrysostom’s explanation of the Church as a hospital is particularly apt and provides us with the keen insight as to the purpose of the Law and the prophets. They show us the way in which we should walk. They show us how to become healthy and how to be whole. They lead us to repentance. And in so doing, they lead us to that place where we can know the God of our hearts. This is the law of the freedom, this is the law of grace, and “until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from” it, thanks be to God.